Popular culture recycles itself every 20 years and Hip-Hop, as it closes on 40, is no different. Chief Keef and his ilk are an example of this. Chicago is enduring one of its most violent years ever. Drill Music, an emerging Chicago bred subgenre of rap, is heavily influenced by that violence. 20 years ago, G-Funk, a musically advanced variant of west coast gangsta music, emerged from the ashes of the L.A. riots. The riots also brought about the Watts gang truce, which seemed to signal the end of one era and the beginning of another.

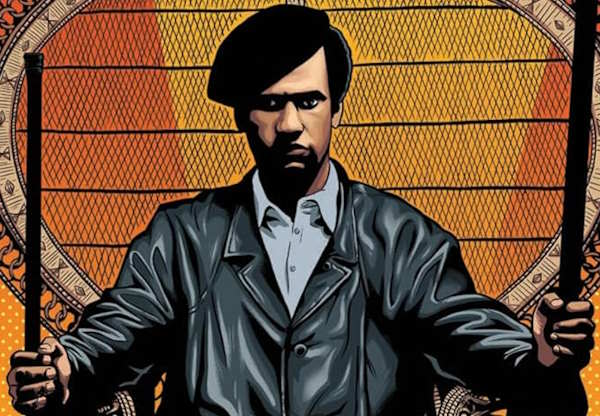

Go back even twenty years further to the early 1970’s, and a similar situation existed in New York City. From 1968 to 1973, gang wars ravaged the Bronx. Between Morris Heights and Soundview, cliques like the Savage Nomads, the Seven Immortals, and the Black Spades waged bloody war. They may not have had automatic weapons, but they certainly had Saturday Night sSpecials and switchblades. Media outlets estimated that there were as many as 100 gangs with over 11,000 members.

In November of 1971, gang warfare kicked into high gear. Among the more visionary of these gangs was The Ghetto Brothers, who eventually transitioned into a peaceful and politically active force. The era culminated with the death of Ghetto Brothers member Cornell “Black Benjy” Benjamin on December 2nd 1971, which inspired the now famous Hoe Avenue Peace meeting that took place five days later. That historic event cleared the way for the coming of new culture that would be based in musical expression. On August 11th, at a “Back to School” Jam hosted by DJ Kool Herc in the rec room at 1520 Sedgewick Avenue, Hip-Hop was born.

To be fair, many saw the Hoe Avenue meeting as nothing more than a PR stunt. Among the skeptics was Ghetto Brothers leader Benjy Melendez. At a subsequent meeting held at the Ghetto Brothers clubhouse, Melendez explained that “It (The Hoe Avenue Peace Meeting) was just a big show. It was for the media to see ‘Oh see, the city got the gangs together.’ But people went out of there feeling angry, feeling pissed off, and it wasn’t genuine.” Indeed, the fighting continued well into 1972, when the NYPD’s Bronx Youth Gang Task force set up shop and declared war. That year, there were 34 gang related homicides in the Bronx.

It’s fair to assume that any knowledgeable Hip-Hopper is familiar with this mythic history. The Bronx of the 1970’s is often painted as a mythic time during which a vibrant new artform emerged. That it was, but there’s another side to the story that often gets downplayed. It has been romanticized in countless books, magazine articles, and documentaries. While Hip-Hop is indeed a wondrous thing, such rose colored reminiscing often downplays an entire side of the culture. The gangs still existed, as did their influence and the conditions that created them. All of those factors played a big hand in shaping Hip-Hop during its infancy.

During the 1970’s, New York City was facing bankruptcy. Like many other areas of New York during that time, the Bronx was awash in Southeast Asian heroin. Shooting galleries, or places where addicts congregated to “shoot up,” were plentiful. In 1973, 40% of residents were on welfare and 30% were unemployed. This was the environment that spawned one of the biggest cultural movements in American history.

Today’s rappers extol the recreational virtues of “Lean” (prescription-strength cough syrup containing codeine and promethazine, mixed with soft drinks and Jolly Rancher candy), various flavors of weed, and “Molly” (MDMA or “Ecstasy”). Hip-Hop’s first decade also had its preferred poisons. When DJ Kool Herc began throwing his now legendary block parties, he’d give unofficial advertisements to the weed merchants in attendance. He’d say “Yo, Johnny, you know I can’t say you got weed, right?” over the microphone, effectively letting the crowd know who had the goods without endorsing such activity.

Today’s rappers extol the recreational virtues of “Lean” (prescription-strength cough syrup containing codeine and promethazine, mixed with soft drinks and Jolly Rancher candy), various flavors of weed, and “Molly” (MDMA or “Ecstasy”). Hip-Hop’s first decade also had its preferred poisons. When DJ Kool Herc began throwing his now legendary block parties, he’d give unofficial advertisements to the weed merchants in attendance. He’d say “Yo, Johnny, you know I can’t say you got weed, right?” over the microphone, effectively letting the crowd know who had the goods without endorsing such activity.

To quote the film Blood In Blood Out, cocaine became America’s “cup of coffee” at some point during the “Me decade.” It was a mainstay on the Disco scene. Hip-Hop, like Punk Rock, is sometimes characterized as having been a reaction to Disco. That may or may not be true, but first generation B-Boys and Girls shared the Disco set’s taste for Cocaine. As block parties became more prevalent, older heads would often congregate in more “exclusive” venues like basements and abandoned buildings. In such places, the air was thick with the aroma of Angel Dust and PCP.

For further evidence of Hip-Hop’s love of cocaine, one only has to consider the rap monikers of the period. Coke La Rock, considered by many to be the first MC, is a great example. In fact, his name had three different iterations, each containing the word “coke.” Ever wondered why Kurt Walker named himself Kurtis Blow? How about the popular rapper surname “ski,” which was used by a great many people back then?

By 1979, the first rap records began to emerge. They were party records, to be sure. But their festive ambiance often allowed racy messages to slip by. Take for example, the now immortal refrain from “Rapper’s Delight”: everybody go hotel motel holiday inn/you say if your girl starts actin up then you take her friend.” No exactly family entertainment, is it? If that isn’t direct enough, there’s Big Bank Hank making boasts such as “he can’t satisfy you with his little worm/but I can bust you out with my super sperm.” Last but not least, the 15 minute version contains perhaps the first ever blasphemous expletive in a hit rap record, Blowfly’s “Rapp Dirty” notwithstanding: “I didn’t even bite and not a god damn word”

That same year, Spoonie G’s debut single “Spoonin’ Rap” added violent threats to the mix:

Say I was breakin and freakin at a disco place

I met a fine girl, she had a pretty face

And then she took me home, you say, “The very same night?”

The girl was on and she was outta sight

And then I got the girl for three hours straight

But I had to go to work, so I couldn’t be late

I said, “Where’s your man?” she said, “He’s in jail”

I said, “Come on baby, cause you’re tellin a tale

Cause if he comes at me and then he wants to fight

See I’ma get the man good and I’ma get him right

See I’ma roll my barrel and keep the bullets still

And when I shoot my shot, I’m gonna shoot to kill

Cause I’m the Spoonie-Spoon, I don’t mess around

I drop a man where he stand right into the ground

The examples given are certainly tame by today’s standards. They aren’t nearly as shocking or profane. However, the often derided content found in modern rap music was still there, if in a more primitive form. As the 70’s transitioned into the 80’s, America became even more decadent and self-absorbed. Hip-Hop’s love affair with cocaine would continue. In fact, it would take huge evolutionary leap thanks to smokable version of the drug. The impact of that little innovation can still be felt in the music to this day. The destruction brought on by the crack era provided fertile ground for the Chief Keefs of the world to one day emerge.

Follow Malice Intended on Twitter @ http://twitter.com/renaissance1977

Follow Us on Twitter @ http://twitter.com/planetill

Join Us on the Planet Ill Facebook Group for more discussion

Follow us on Networked Blog