By Odeisel

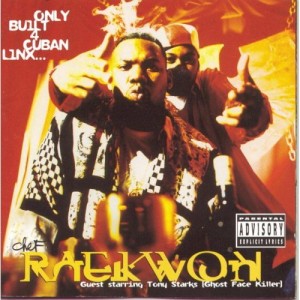

Hip-Hop is that most curious of arts, where content isn’t necessarily a detriment to praise. Much like movies, where the themes of sex and violence propel many films to high grossing numbers and critical acclaim, so does Hip-Hop prosper from the projection of our darkest dreams or in many cases our forbidden realities. In 1995, following a rash of very strong albums in the early 90s, Raekwon the Chef along with partner in rhyme Ghostface Killah with an assist from the rest of their Clan, came up with an album that changed the face of Hip-Hop and immediately cast a purple shadow over its contemporaries.

By 1994, the Daisy Age was effectively dead, even though there were some pretty strong Native Tongue albums during that time period. The Chronic juggernaut forced Hip-Hop on to MTV by adding melody to mayhem, while on the East Coast, the gritty realism of albums like Illmatic, Ready To Die, and The Infamous pushed urban dystopia with rich depth and a darker disposition. Rather than take the music further down reality road, Rae and Ghost took us back to the movies with Only Built 4 Cuban Linx.

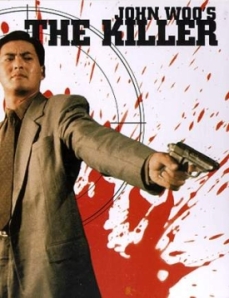

Inspired by Hong Kong crime thrillers of the Late 80s such as Hard Boiled and The Killer, and cult classic b-movies like Scarface, OB4CL sprinkled a bit of hood on top, and delivered a next level action film on wax.  The story itself is a retread: an aging criminal looking for one final big score so he can retire and run off into the sunset. It’s the execution and the panache of it that makes this album classic and one of the greatest ever.

The story itself is a retread: an aging criminal looking for one final big score so he can retire and run off into the sunset. It’s the execution and the panache of it that makes this album classic and one of the greatest ever.

We must begin with the production. There are numerous clips and interludes interspersed with dialogue from movies such as The Mack,and Shaolin Vs. Lama to further the cinematic feel, and add a bit of camp, perhaps to offset how real the subject matter felt. It was clear that while some members of the clan were involved in “extracurricular” activities, OB4CL was in truth cinema and not autobiographic.

Aside from the movie clips, the RZA took a different production approach to this album. There are more strings on it and harder drums with the effect of heightening melancholy and somberness while maintaining aggression respectively. There were more soul samples on this release than the previous Wu albums, which added emotional depth. Each song is rendered like a scene and the album overall feels like a score as each song pushes along the story while changing in pace and mood. It’s very well sequenced; pulling you in with the intro, allowing the interludes to give background to the story and each individual song ramping up action in the present tense, or accounting for story in the past tense, delivering a clear narrative in conversational first person (Ghostface in “Can It Be All So Simple RMX”) or third person adrenaline rushed chronicles (“Spot Rushers”).

Lyrically, both Raekwon and Ghostface showcased far more than they were allowed on the crowded 36 Chambers. The raw delivery, coupled with their distinct voices was augmented by Five Percent lingo and Staten Island slang. The guest appearances are all well placed, from U-God’s brief contribution on the opening song, to Nas’ classic verse from the minimalist “Verbal Intercourse.” The guest emcees serve as method actors; each delivering their role with well-directed brilliance.

Aside from the waves the album created, there is also its legacy that you have to consider when determining its place in history. Albums that powered the center of the second golden age are at very least informed by this album if not inspired by it. The Wu-Gambino-driven wise guy themes inspired a slew of alias driven albums most notably It Was Written, helmed by Nas Escobar, and the hustler’s love letter Reasonable Doubt, not to mention Biggie’s transformation into “The Black Frank White.” No longer did you have to have a bad ending for these kinds of stories.  The brilliance of Cuban Linx, much like the aforementioned Scarface allowed people to see themselves as and root for the bad guy; a stark departure from Hip-Hop like Ice-T’s “High Rollers”, Slick Rick’s “Children’s Story,” and BDP’s “Love’s Gonna Get You” where the criminals always flamed out in consequence to their fiery lives. There was no social relevance or “ghetto CNN” covers of Ice Cube and early N.W.A. or even cartoonish sinister tales of gangsta life that permeated the first wave of Death Row releases. This was crime rhyme for its own sake, and it was so brilliantly delivered that it didn’t need a moral compass.

The brilliance of Cuban Linx, much like the aforementioned Scarface allowed people to see themselves as and root for the bad guy; a stark departure from Hip-Hop like Ice-T’s “High Rollers”, Slick Rick’s “Children’s Story,” and BDP’s “Love’s Gonna Get You” where the criminals always flamed out in consequence to their fiery lives. There was no social relevance or “ghetto CNN” covers of Ice Cube and early N.W.A. or even cartoonish sinister tales of gangsta life that permeated the first wave of Death Row releases. This was crime rhyme for its own sake, and it was so brilliantly delivered that it didn’t need a moral compass.

You would be hard pressed to find a Hip-Hop album without cultural morality or importance of some level that could be matched against the purple tape. It was genius in construction and execution both musically and lyrically. It is mammoth even while lacking the artistic forwardness of an Aquemini, or the social power of an It Takes A Nation of Millions. It is not a sonic leap forward like The Chronic or The Low End Theory. It is however, arguably the best hardcore Hip-Hop album of all-time. It stood out among its contemporaries during a period of very high quality competition, and forced both friends and enemies in their periphery to change their style. It is the guiltiest of pleasures, and allows us to revel in our visions of criminality without having to immerse ourselves. It is the ultimate experience in Black hood voyeurism. Let’s hope the sequel can approach this level of excellence.

Follow Us on Twitter @ http://twitter.com/planetill

Follow Odeisel on Twitter @ http://twitter.com/odeisel

Join Us on the Planet Ill Facebook Group for more discussion

2 thoughts on “OB4CL: Greatest Hardcore Hip-Hop Album?”