Officially, there is no caste system in America. Those who occupy the middle and lower classes of this great nation know better. Class warfare is as American as apple pie, baseball, and racism. In the African-American community, it manifests itself in a very particular and troubling way: The ongoing conflict between so-called “Field Negroes” and “House Negroes.”

The latest eruption of this conflict can be seen in the ongoing discourse surrounding Quentin Tarantino’s controversial Spaghetti Western Django Unchained. Ever since the project was announced, it has been a lightning rod for controversy. When it was still in screenplay form, many took exception to its incessant use of the word nigger. Two days before its Christmas release date, Spike Lee made his feelings known in an interview with VibeTV. When asked about the film, Lee said that he wouldn’t be seeing it, as doing so would be disrespectful to his ancestors. Via his twitter account, he took exception to the film’s very premise.

Lee’s comments drew immediate fire, which has raged ever since. Comedian turned activist and health guru Dick Gregory praised the film, and derided Lee as a “punk.” He also referred to the films in Lee’s oeuvre as “thug movies.” More vitriolic was Luther “Uncle Luke” Campbell’s op-ed in The Miami New Times, titled “Spike Lee Is No Quentin Tarantino.” In it, he refers to Lee as “Hollywood’s resident house Negro; a bourgeoisie activist who wants to tell his fellow white auteurs how they can and can’t depict African-Americans.” Luke concludes his rant by calling Lee “a conniving and scheming Uncle Tom.” Django Unchained star Jamie Foxx recently joined the fray, calling Lee “shady” and “irresponsible” in an interview with The Guardian. As of this writing, no compromise of any sort has been reached between Lee and his detractors.

Though American slavery was officially abolished 147 years ago, the war between House Negros and Field Negros rages on with no end in sight. The phenomenon is, in fact, a direct result of slavery. Field Negroes toiled out in the hot sun, and were subjected to all manner of torture and subhuman treatment. House slaves, on the other hand, worked in the comfort of the “Big House.” They catered to the needs of the master, and often served as the master’s right hand. The head house slave, often referred to as the HNIC (Head Nigger In Charge), would delegate work and dole out punishment to those lower on the plantation hierarchy.

In his February 4th, 1965 speech to the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in Selma, Alabama, Malcolm X famously put the House Negro mindset into its proper perspective:

“If the master’s house caught on fire, the house Negro would fight harder to put the blaze out than the master would. If the master got sick, the house Negro would say, “What’s the matter, boss, we sick?” We sick! He identified himself with his master more than his master identified with himself. And if you came to the house Negro and said, ‘Let’s run away, let’s escape, let’s separate,’ the house Negro would look at you and say, ‘Man, you crazy. What you mean, separate? Where is there a better house than this? Where can I wear better clothes than this? Where can I eat better food than this?’ That was that house Negro. In those days he was called a ‘house nigger.’ And that’s what we call him today, because we’ve still got some house niggers running around here.”

Ironically, the third act of Django Unchained offers a prototypical “House Nigger.” (Warning: Major Spoilers Ahead) Upon entering the massive plantation known as Candyland, Django Freeman and Dr. King Schultz confront a deceptive and hateful House slave named Stephen. The conflict between Django and Stephen soon becomes the focal point of the film.

To be clear, I absolutely adore Django Unchained. I think it’s among Quentin Tarantino’s best work. I have written a small handful of pieces that simultaneously sing its praises and defend it on my personal blog. However, I have recently placed a moratorium on such activities, due to the discourse taking such an ugly turn. Though I wholeheartedly disagree with Spike’s assessment of the film, and have taken him to task for it, the words of his detractors have caused me to wince.

I initially found Luther Campbell’s comments hilarious. When relaying the then breaking news to a friend of mine, I coukdnt stop laughing. Finally, someone was calling out Lee for what he was. However, I soon began to sober up. While I can certainly understand where Luke is coming from, he crossed a line.

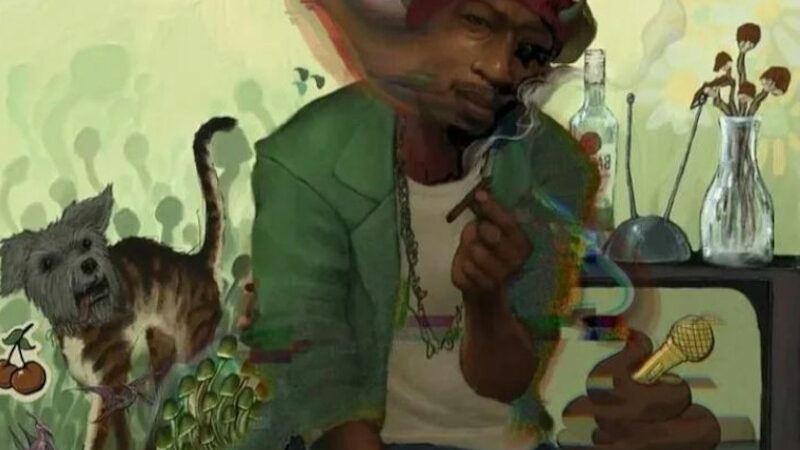

Luke’s conflict with Spike stretches back well over 20 years. Spike had some rather unkind words for Luke and company while being interviewed by Fab 5 Freddy on YO! MTV Raps. Luke later responded with “I Ain’t Bullshittin’ III” from the 2 Live Crew’s 1991 album Sports Weekend: As Nasty as They Wanna Be, Pt. 2. Surprisingly, Campbell gave the filmmaker something of a pass, stating that the situation between them had been squashed.

Whatever common ground the two managed to find back then seems to have given way over the past couple of decades. Invoking House Negro/Field Negro imagery is nothing new for Campbell. He did the same thing back in 1992 during his beef with Kid ‘N Play. His sophomore solo album, I Got Shit on My Mind, contained the scathing diss track “Pussy Ass Kid and Hoe Ass Play (Payback is a Mutha Fucker).” In true Luke fashion, he closed the song with an extended and profane rant:

“Two house motherfuckin’ niggas. Do y’all niggas know what a house nigga is? A house nigga is a nigga who work in the house. Who cleans the master’s ass, who cleans behind the master, who wash the master’s ass. Y’all house niggas. I’m a field nigga, we field niggas here in Miami.”

Campbell is hardly alone in employing such terminology when engaging fellow Black folks in verbal combat. In recent years, brothers have become all too comfortable casting such aspersions at one another. As if calling each other “niggas” in mixed company wasn’t bad enough, other racial epithets and insults have been added to the mix. A quick glance at any messageboard catering to our community reveals that brothers are very quick to label a perceived sell-out as a “coon,” “Uncle Tom,” or “House Nigga.” Not only are we no longer shy about airing our dirty laundry in public, but we do so with vigor.

Interestingly, labeling another Black Person as an “Uncle Tom” in an attempt to accuse them of selling out is a misapplication of the term. It also betrays the ignorance of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which helped to popularize the term as a popular insult. In Beecher’s story, it was the character of Sambo, and not Uncle Tom, who was the sell-out. Sambo was an overseer, and as such, complicit in the evil of American slavery.

Make no mistake about it, Spike Lee is surely insufferable. He’s arrogant and overly outspoken, and his relevance in the current era is questionable at best. I can see where both Dick Gregory and Luther Campbell are coming from, and I sympathize with their position on the matter. I too have grown weary of Spike’s antics. However, I cannot condone the nature of such infighting in its current form. To question another Blackman’s loyalty and/or love for his people is an insult of the highest order.

The war between the House Negro and Field Negro must end. We are one people, and as such, part of the same struggle. We should be able to disagree amongst ourselves without all this nonsense.

Follow Malice Intended on Twitter @ http://twitter.com/renaissance1977

Follow Us on Twitter @ http://twitter.com/planetill

Join Us on the Planet Ill Facebook Group for more discussion

Follow us on Networked Blog